In the intricate world of software development and project management, success is often measured by more than just whether a system “works.” It’s about how well it works, under what conditions, and with what level of quality. These crucial, yet frequently underestimated, aspects are encapsulated within non-functional requirements (NFRs). They are the silent architects of user satisfaction, system resilience, and operational efficiency, defining the very character of a product or service.

Ignoring these critical elements can lead to a product that is functionally sound but ultimately unusable, insecure, or incapable of scaling to meet demand. Imagine a lightning-fast e-commerce site that crashes under peak load, or a robust data management system that’s impenetrable but impossible to navigate. A structured approach to capturing these elusive yet vital requirements is not just beneficial; it’s essential for mitigating risks, avoiding costly rework, and delivering a truly successful outcome.

Why Non-Functional Requirements Are Non-Negotiable

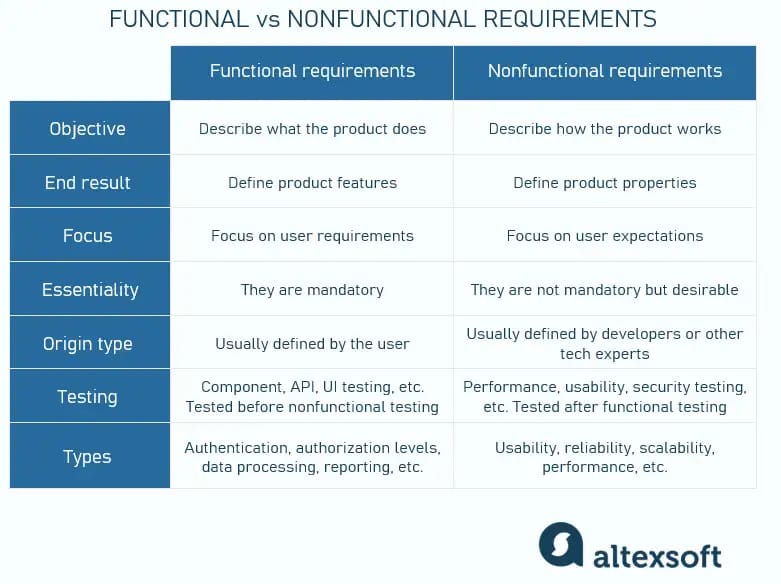

While functional requirements dictate what a system *does*, non-functional requirements (NFRs) specify how a system *performs*. They are the quality attributes that define the system’s operational characteristics, such as speed, security, usability, reliability, and scalability. Often, these are the very qualities that differentiate a merely acceptable product from an exceptional one, directly impacting user experience and business value. Neglecting NFRs during the early stages of a project can result in significant technical debt, unexpected costs, and a product that fails to meet stakeholder expectations, despite delivering all its core functions.

Think of it this way: functional requirements define the car’s ability to drive, brake, and steer. Non-functional requirements define its fuel efficiency, crash safety rating, acceleration from 0-60 mph, and the comfort of its interior. Without a clear understanding of these quality attributes, development teams might build a car that drives but is unsafe, incredibly slow, or extremely uncomfortable, leading to eventual rejection by its intended users. Investing time upfront to define these system quality attributes is a proactive measure that saves time, money, and reputation in the long run.

The Anatomy of Effective Non-Functional Requirements

For NFRs to be truly effective, they must be more than just vague aspirations like “the system should be fast.” They need to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Each non-functional specification should clearly articulate an expectation and provide a means to verify whether that expectation has been met. This level of detail ensures that development teams have clear targets and that testing teams can validate the system’s adherence to these critical quality benchmarks.

A well-defined non-functional requirement might state, "The system shall process 95% of user login requests within 2 seconds under a load of 1,000 concurrent users." This statement is precise, includes measurable metrics (95%, 2 seconds, 1,000 concurrent users), and implies a timeframe for evaluation. Without such specificity, NFRs remain subjective and open to interpretation, making it difficult to design, implement, and test the system adequately. Capturing these details systematically is a cornerstone of robust project delivery.

Key Categories of Non-Functional Requirements

Non-functional requirements span a broad spectrum, covering various aspects of system quality and operational performance. Grouping them into categories helps ensure comprehensive coverage and makes the documentation more organized and digestible. While specific categories might vary slightly between projects or industries, a common set typically includes:

- Performance: How quickly and efficiently the system responds to user input and processes data. This includes response times, throughput, and resource utilization.

- Scalability: The system’s ability to handle an increasing amount of work or its potential to be enlarged to accommodate growth. This might involve supporting more users, data, or transactions.

- Security: Measures to protect the system and data from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction. This covers authentication, authorization, data encryption, and vulnerability management.

- Usability: How easy it is for users to learn, operate, and be effective with the system. Factors include user interface design, learnability, error handling, and accessibility.

- Reliability: The probability that the system will perform its intended functions without failure for a specified period under specified conditions. This includes availability, fault tolerance, and recovery capabilities.

- Maintainability: The ease with which the system can be modified, enhanced, corrected, or adapted to changes in the environment. This considers modularity, code quality, and documentation.

- Portability: The ease with which the system or its components can be transferred from one hardware or software environment to another.

- Availability: The proportion of time a system is functional and operational. This is often expressed as a percentage (e.g., 99.9% uptime).

- Compliance: Adherence to relevant laws, regulations, industry standards, and internal policies (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA, PCI DSS).

Each of these categories plays a crucial role in defining the overall quality and suitability of a system for its intended purpose.

Leveraging a Structured Approach to NFRs

The journey from vague aspirations to clear, measurable non-functional specifications can be challenging. This is precisely where a well-designed **Non Functional Requirements Template** proves invaluable. Such a template provides a structured framework, acting as a comprehensive checklist that guides stakeholders through the process of identifying, documenting, and prioritizing critical system attributes. It ensures consistency across projects, reduces the likelihood of overlooking essential quality concerns, and streamlines communication among diverse teams, from business analysts to architects, developers, and quality assurance.

A good requirements template typically organizes NFRs by category, prompts for specific metrics, and encourages the definition of acceptance criteria. This systematic approach transforms the often-abstract discussion of quality into concrete, actionable requirements. By using a pre-defined structure, organizations can standardize their approach to documenting non-functional aspects, making it easier to compare projects, identify common issues, and build institutional knowledge over time. It shifts the focus from ad-hoc discussions to a deliberate, thoughtful exploration of a system’s quality and operational characteristics.

Building Your Custom NFR Framework

While a generic non-functional requirements template provides an excellent starting point, the most effective approach often involves customizing it to fit the unique context of your organization and specific projects. Not all NFR categories hold equal weight for every system. A banking application will have stringent security and reliability requirements, whereas a marketing website might prioritize performance and usability. The customization process involves tailoring the template’s sections, adding industry-specific examples, and refining the metrics that matter most to your business objectives.

Consider the nature of your projects, your development methodology, and the maturity of your team. For instance, an agile team might prefer a more concise template that can be integrated into sprint planning, while a heavily regulated industry might require a more exhaustive document for audit purposes. Involve key stakeholders in the customization process to ensure the framework aligns with everyone’s expectations and operational realities. This collaborative effort transforms a generic document into a powerful tool that resonates with your specific needs, making the task of defining project quality attributes an integrated part of your development lifecycle rather than an afterthought.

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Even with a robust framework, the process of defining and managing NFRs can encounter challenges. Avoiding common pitfalls and adhering to best practices can significantly enhance the effectiveness of your non-functional requirements gathering.

Common Pitfalls:

- Vague Language: Using terms like “fast” or “user-friendly” without quantifiable metrics.

- Overlooking Stakeholders: Failing to involve all relevant parties (e.g., operations, security, legal) early in the process.

- Late Definition: Waiting until design or development phases to define critical non-functional specifications.

- Lack of Prioritization: Treating all NFRs with equal importance, leading to scope creep and unmanageable expectations.

- No Measurement Strategy: Defining NFRs without considering how they will be tested or validated.

Best Practices:

- Involve All Stakeholders Early: Gather input from business users, architects, operations, security, and legal from the outset.

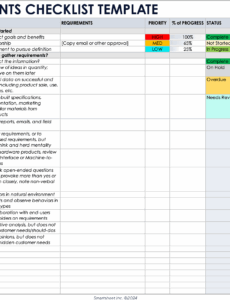

- Prioritize NFRs: Categorize requirements by criticality, distinguishing between “must-haves” and “nice-to-haves” using techniques like MoSCoW.

- Make Them Measurable and Testable: Ensure each NFR has clear metrics and acceptance criteria, allowing for objective validation.

- Iterate and Refine: NFRs are not static; review and update them throughout the project lifecycle as understanding evolves.

- Document Clearly: Use consistent terminology and a well-structured document to avoid ambiguity.

- Integrate into Design and Testing: Ensure NFRs influence architectural decisions and form a core part of your testing strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between functional and non-functional requirements?

Functional requirements describe what the system *should do*, outlining specific behaviors or functions. For example, “The system shall allow users to log in.” Non-functional requirements, in contrast, describe *how well* the system performs those functions, focusing on quality attributes like “User login shall complete within 2 seconds.”

Why are NFRs often overlooked in projects?

NFRs are often overlooked because they are less tangible than functional requirements and can be harder to define and measure. Project teams might prioritize immediate feature delivery over less visible quality attributes, leading to technical debt and performance issues later on. The absence of a structured non-functional requirements template or framework can also contribute to this oversight.

Who is responsible for defining non-functional requirements?

Defining NFRs is a collaborative effort. While business analysts or product owners may initiate the process, critical input comes from architects (for technical feasibility), operations teams (for maintainability and availability), security experts (for security guidelines), and end-users (for usability criteria). It’s a cross-functional responsibility to ensure all aspects of system quality are covered.

Can non-functional requirements change during a project?

Yes, NFRs can and often do evolve throughout a project’s lifecycle. As business needs shift, technology advances, or user feedback emerges, certain non-functional specifications might need to be adjusted. It’s crucial to have a process for managing changes to these requirements, just as you would for functional ones, to ensure the system remains aligned with current expectations.

How do you measure non-functional requirements?

Measuring NFRs involves defining clear metrics and acceptance criteria for each requirement. For instance, performance can be measured by response time in milliseconds, scalability by the number of concurrent users supported, and reliability by uptime percentage. These measurements often require specific testing tools, performance benchmarks, security audits, and user experience studies to validate.

Mastering the art of defining and managing non-functional requirements is a hallmark of mature software development and project management. It transforms a product from merely functional to truly exceptional, ensuring it not only meets business objectives but also delights users and operates reliably under diverse conditions. The effort invested in systematically documenting these critical system quality attributes pays dividends in reduced risk, higher user satisfaction, and a more robust, future-proof solution.

Embracing a structured NFR framework, whether through a formalized template or a custom-built system, empowers teams to build with purpose and precision. It fosters a culture where "how well" is as important as "what," leading to systems that are not just built right, but also built for success. Start today by evaluating your approach to these vital requirements and consider how a dedicated Non Functional Requirements Template could elevate your project outcomes.