Embarking on a new software development project, whether it’s a mobile app, a complex enterprise system, or a simple web tool, can feel like navigating uncharted waters. Without a clear map, even the most skilled development team can get lost, leading to scope creep, missed deadlines, budget overruns, and ultimately, a product that doesn’t quite meet its intended purpose. The root cause of these challenges often boils down to a fundamental lack of clarity and agreement on what the software is actually supposed to do.

This is precisely where a robust framework for defining project needs becomes indispensable. Imagine a blueprint for your software, detailing every feature, function, and constraint before a single line of code is written. That’s the power of a well-crafted requirements document. It transforms vague ideas into concrete specifications, ensuring everyone involved – from stakeholders to developers and testers – shares a unified understanding of the project’s goals and deliverables.

Why a Well-Defined Requirements Document is Crucial

In the fast-paced world of software development, it’s tempting to jump straight into coding. However, skipping the crucial step of thoroughly defining requirements is akin to building a house without an architect’s plans; you might end up with something functional, but it’s unlikely to be what was originally envisioned, and fixing issues later becomes exponentially more expensive and time-consuming. A comprehensive requirements document serves as the bedrock for the entire software development lifecycle.

It acts as a single source of truth, mitigating misunderstandings and misinterpretations that can plague projects. When requirements are ambiguous or poorly communicated, teams can waste valuable time developing features that aren’t needed or missing critical functionalities. A structured approach to documenting these needs not only saves resources but also significantly improves the likelihood of project success and stakeholder satisfaction.

Key Benefits of Using a Standardized Requirements Document

Adopting a standardized approach, like utilizing a tailored requirement document template for a software project, brings a multitude of advantages. It fosters consistency across projects and teams, streamlining the documentation process and making it easier for new members to onboard. Beyond mere efficiency, the benefits permeate every stage of development.

Clear and unambiguous specifications lead to more accurate estimates for time and cost. They provide a solid foundation for designing the system architecture, creating test plans, and ultimately, for verifying that the final product meets all specified criteria. This proactive approach minimizes costly rework and ensures the end product aligns perfectly with business objectives.

- Improved Communication: Establishes a common language and understanding among all project stakeholders.

- Reduced Rework: Identifying discrepancies and ambiguities early prevents costly changes late in the development cycle.

- Enhanced Quality: Provides a clear benchmark for testing, ensuring the software performs as expected and meets quality standards.

- Better Project Management: Offers a reliable basis for planning, scheduling, and tracking project progress.

- Risk Mitigation: Helps identify potential technical or business risks upfront, allowing for proactive planning.

- Stakeholder Alignment: Ensures that the final product addresses the specific needs and expectations of all involved parties.

Core Components of an Effective Software Requirements Document

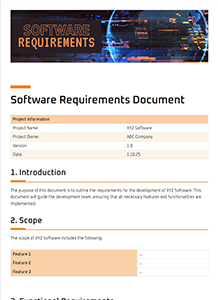

While the exact structure of a software project requirements outline can vary based on project complexity and methodology, certain core components are universally recognized as essential. These sections ensure a holistic view of the system, covering everything from its overarching purpose to granular technical details.

A robust software requirements specification (SRS) template typically begins with the "why" before delving into the "what" and "how." It carefully balances business needs with technical feasibility, acting as a crucial bridge between different disciplines. Understanding these components is the first step towards creating a document that truly serves its purpose.

- Introduction: Briefly describes the document’s purpose, scope, and target audience. It also outlines the overall vision and goals of the software project.

- Overall Description: Provides a high-level overview of the product, its users, and the environment in which it will operate. This includes:

- Product Perspective: How the software fits into the larger system or business context.

- Product Functions: A summary of the major functions the software will perform.

- User Characteristics: Who will use the software and their relevant attributes (e.g., technical proficiency).

- General Constraints: Any limitations or influences (e.g., regulatory requirements, hardware limitations, existing systems).

- Assumptions and Dependencies: Factors assumed to be true or external elements the project relies upon.

- Functional Requirements: This is the heart of the document, detailing what the system must do. These are specific actions the software should perform, often expressed as user stories or use cases. Each requirement should be clear, verifiable, and unambiguous.

- Non-Functional Requirements: Describes how the system should perform. These are criteria that judge the operation of the system, rather than specific behaviors. Examples include:

- Performance: Response times, throughput, resource usage.

- Security: Authentication, authorization, data protection.

- Usability: Ease of learning, efficiency of use, user interface design standards.

- Reliability: Uptime, error rates, recoverability.

- Scalability: Ability to handle increased load or data volume.

- Maintainability: Ease of modifying, extending, or fixing the software.

- Portability: Ability to run on different environments.

- External Interface Requirements: Details how the software will interact with users, hardware, other software systems, and communication interfaces.

- Data Model (Optional but Recommended): Describes the structure and relationships of the data that the software will store and manage.

- Appendices: May include glossary of terms, indexes, or supporting documents.

Practical Tips for Customizing and Utilizing Your Template

While a standardized framework for software project documentation is invaluable, effective utilization demands customization and an iterative approach. A template is a starting point, not a rigid prison. Tailoring it to the specific needs and context of your project is key to its success.

Start by reviewing each section of your chosen template and deciding its relevance. Some smaller projects might not need an exhaustive data model, while highly secure systems will demand extensive non-functional specifications. The goal is clarity and utility, not just filling out every blank.

- Tailor to Project Scope: A simple web app doesn’t need the same level of detail as a mission-critical enterprise system. Customize the depth and breadth of each section based on your project’s complexity and team size.

- Involve Stakeholders Early and Often: Requirements gathering is a collaborative process. Engage end-users, product owners, and technical leads from the outset to ensure all perspectives are captured and agreed upon.

- Prioritize Requirements: Not all features are equally important. Use techniques like MoSCoW (Must have, Should have, Could have, Won’t have) or simple numbering to help the development team focus on the most critical elements first.

- Make it Living Document: A requirements document isn’t a static artifact. It should evolve with the project. Establish a process for review, updates, and version control to reflect changes and new insights.

- Use Clear, Concise Language: Avoid jargon where possible. If technical terms are necessary, include a glossary. Each requirement should be unambiguous, leaving no room for subjective interpretation.

- Focus on the "What," Not the "How": While some architectural constraints might be necessary, the primary focus of an SRS is to describe what the system must do, leaving the how to the design and development phases.

Beyond the Template: Best Practices for Requirements Gathering

Having a solid document structure is only one piece of the puzzle. The process of actually gathering and validating those requirements is equally critical. Effective requirements engineering goes beyond merely filling out sections; it involves active listening, critical thinking, and continuous refinement.

Techniques like interviewing stakeholders, conducting workshops, analyzing existing systems, and creating user stories or use cases are vital. In agile environments, the product backlog serves as a dynamic, prioritized list of requirements, often expressed as user stories, which are then refined and elaborated upon over time. Regardless of the methodology, the essence remains the same: understand the problem thoroughly before attempting to build the solution.

Regular communication, feedback loops, and prototyping can also play a significant role. Prototypes and mock-ups can help stakeholders visualize the proposed solution, making it easier to identify gaps or mismatches with their expectations early on. This iterative approach to defining software needs ensures that the final product is not just technically sound, but truly valuable to its users.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a Requirements Document and a Product Backlog?

A requirements document, often a Software Requirements Specification (SRS), is a comprehensive, typically formal document detailing all functional and non-functional requirements for a software product. It aims to be exhaustive. A product backlog, primarily used in agile methodologies, is a dynamic, prioritized list of features, functions, enhancements, and bug fixes that need to be delivered. It’s less formal and evolves continuously, with details often elaborated just-in-time.

When should I create a software requirements specification?

Ideally, a software requirements specification should be created at the very beginning of a project, after the initial concept and feasibility studies are complete, but before design or development begins. For larger or more complex projects, a detailed SRS is crucial. In agile contexts, requirements are continuously refined, but an initial understanding of the project’s vision and core needs is still documented, often through a product vision and initial backlog.

Can a single template work for all types of software projects?

While a core requirement document template for a software project provides a great starting point, it will almost always need customization. The level of detail and specific sections required will vary significantly depending on factors like project size, complexity, regulatory compliance needs, the chosen development methodology (e.g., Waterfall vs. Agile), and the type of software being developed (e.g., embedded system vs. web application). It’s best to adapt the template to suit your specific context.

Who is responsible for writing the requirements document?

The responsibility typically falls to a Business Analyst, Product Owner, or System Analyst. However, it’s a collaborative effort. These individuals facilitate the gathering process, elicit information from stakeholders (users, business owners, technical leads), and then compile and articulate those needs into the document. Approval usually involves key stakeholders, project managers, and lead developers.

A well-articulated framework for defining project needs is not just a bureaucratic hurdle; it’s an empowering tool that drives clarity, efficiency, and ultimately, success in software development. By leveraging a comprehensive requirement document template for a software project, you lay a solid foundation that supports every subsequent stage of development, from design and coding to testing and deployment. It acts as the anchor that keeps your project aligned with its vision and your team focused on delivering genuine value.

Embrace the discipline of thorough requirements definition. It’s an investment that pays dividends by minimizing costly missteps, fostering better collaboration, and ensuring that the software you build genuinely solves the problems it was intended to address. Equip your team with this essential blueprint, and watch your software projects transform from ambiguous endeavors into clear, successful achievements.